This year, I pledged to make some dang apps again, but unlike the apps that I did for my startup years ago, these would be things made in no one’s interest but my own. I wanted to know: could technology, deliberately made and applied, allow me to connect with some important part of myself?

This post is the first in a series. Eventually, you can read about the other apps here.

![]()

I have a problem with spending. Like most things in my life, it fluctuates wildly as a counterforce to give me emotional stability. Money can do many things: chiefly, it can add novelty and surprise and promise and hope. It promises transformation with no other effort required than the spending of it.

The problem comes when I fail to actually hear what I need, or actively crush and abandon those feelings, and then use money to make up the difference. What hope can you have for feeling whole and happy if you live in constant denial of your needs, always trying harder and with higher stakes to make up for not having listened to yourself in the first place? We’ll get to why I do that in another post, maybe, but it should suffice to say: there are a lot of reasons why it’s hard for me to hear myself.

So what’s the solution? The only real one is to live a life in connection to myself. That means eroding all the old patterns that I readily jump into, whose siren call sounds much like salvation, but really is just another way to believe that I’ll be made okay if I ignore myself just this one last time. It means also (and more importantly) staying in connection with myself even when it’s hard, as if to say: I’m the sort of person who cares about himself enough to actually act that way.

But then sometimes, in moments of acute challenge, it can be nice to have a system that lets me know when I’m leaning on money again, and to help me understand why.

My system revolves around using You Need A Budget (colloquially: YNAB) to track spending, budget, plan for future spending, and practice good financial behaviours with a minimum of stressing and ruminating. I use it as their documentation prescribes: always aiming to have all of next month’s expenses saved up by the time this month is up, tracking spending as close to as it happens as possible so I have a clear sense of what money I have left, and giving every dollar a job – even if that job is to sit in a “holding category” until I see where it could best be used in my life.

And that’s where I realized there was a bit of a gap in YNAB’s functionality. It uses categories to track what you’ve spent money on: your Rent category is where you add money to your budget to cover your rent, and it’s where you add a transaction to take that money away and send it to your mediocre landlord. YNAB is great at helping you define the buckets where you’ll spend money in the future – but that’s not really the issue for me.

My issue is not with a bucket or a category. My issues is with things. Specific things. Things that promise what my self asked for and was denied. Things that offer a hope of connecting to what I wanted all along. Things that can do for me what I couldn’t do for myself. For my budgetary alarm system to work, it needs to let me track what things begin to take this shape.

And, boy, have there been things. The Teenage Engineering OP-1, a beautiful portable synthesizer I bought for around $1200 in May 2014 as my startup was falling apart and I was on my last few thousand dollars, was my expensive way of saying: I have spent three years building music startups that I convinced myself I wanted to build, when I really just want to make fucking music.

My trip to the Philippines in late 2017, after I quit a job that I’d stayed in against my better judgment merely to prove to myself that I could last a year in a job, was an endless parade of moments that I indulged in and paid for and fantasized endlessly about and which were supposed to make me feel whole again after having ignored my every impulse for not just the tenure of that job, but of the one before it, and the one before it. No fantasy ripens as sweet as a fantasy postponed.

I’m using “things” to conflate experiences and actual corporeal things, because, honestly, it doesn’t matter. There are endless lightly-researched thinkpieces that implore you to pursue experiences over things, but if you’re just looking for a fix that will quiet a restless and spurned self, I can tell you that what’s more important is what in you that thing stands in for: what you won’t give yourself. It could be a specific popsicle. It doesn’t matter, as long as you’re spending money on it and it promises salvation and reconnection and a truth you’ve long denied.

So. Money. It’s intimately connected to my continuing willingness to abandon myself for pretty much anyone else’s anything. And that means that I can take my urges to spend for what they really are: sublimated needs, calling out desperately.

Noticing that my urges to spend are promptings to get back into touch with myself and my needs means that I should pay very careful attention to them. It’s also a practical financial solution: rather than simply indulging those urges whenever they come up, which can get very expensive and is typically most expensive right as my financial situation is most precarious, I need to triage whether they’re smart or not, or whether I could meet that need by, perhaps, giving myself the solution to the need itself, rather than just buying another thing that promises to do that.

Introducing: Ynabby

To help me do that, I built an iOS app that would help me document and prioritize my spending on these needful things, which would also connect to YNAB so that I could tell whether or not I had the money to spend, and what it would trade off against.

It’s called Ynabby. It’s been through two iterations – the first ended up being far too focused on the budget categories in YNAB. I’d create an item I’d like to buy, add it to the relevant spending category (like Rent or Shopping or Dream Cruise), and then would look at the list of the other items in that category to prioritize it.

But I realized that wasn’t super helpful – there was no view of all my wantings together. These things might be a vacation, or a musical instrument; they might be a thing or an experience or a cause or a charity. All of those are plausible things that belong in many different categories. But all of them promised the same release, and they all pulled from the same paycheque. What’s to say that this month isn’t going to be a month where I’ll feel most compelled to spend money on Home Furnishings rather than Clothing? In the old way, I’d hide my true spending in many tiny little sneaky buckets.

So I redesigned the app to list every potential thing I wanted to buy, from all the categories I could buy them in, all in the same list. That way, spending money on one forced me to consider whether I’d rather spend it elsewhere. Prioritizing started to feel much more honest – sunlight got to all of my wants equally.

Here’s what the current version looks like – here, I appear to be realizing I want to cook tasty things again:

The cells even act as neat progress bars: if it’s a big thing, I show just how much money I have saved up towards it by filling the background in the appropriate colour from left to right.

Hearing my wallet talk

The last feature I added is where it all came together into an app that doesn’t just let me see what I want to spend money on – but which helps me connect with my forgotten, sidelined self.

I think we’ve established that spending money has never just been about financial reality or pragmatism for me. So sure, it’s great to know how much I can spend at a given moment, and have some help prioritizing what to spend it on. But that alone isn’t enough.

Money has been a stand-in for everything about myself I couldn’t accept and pursue. So I figured I could actually use these dangerous impulses to help me do what I really needed: to see what I’d been denying myself. By treating my spending temptations as indications that I was ignoring my needs, I could begin to ask what it was I actually was after, underneath all the dollar signs and hopes of things.

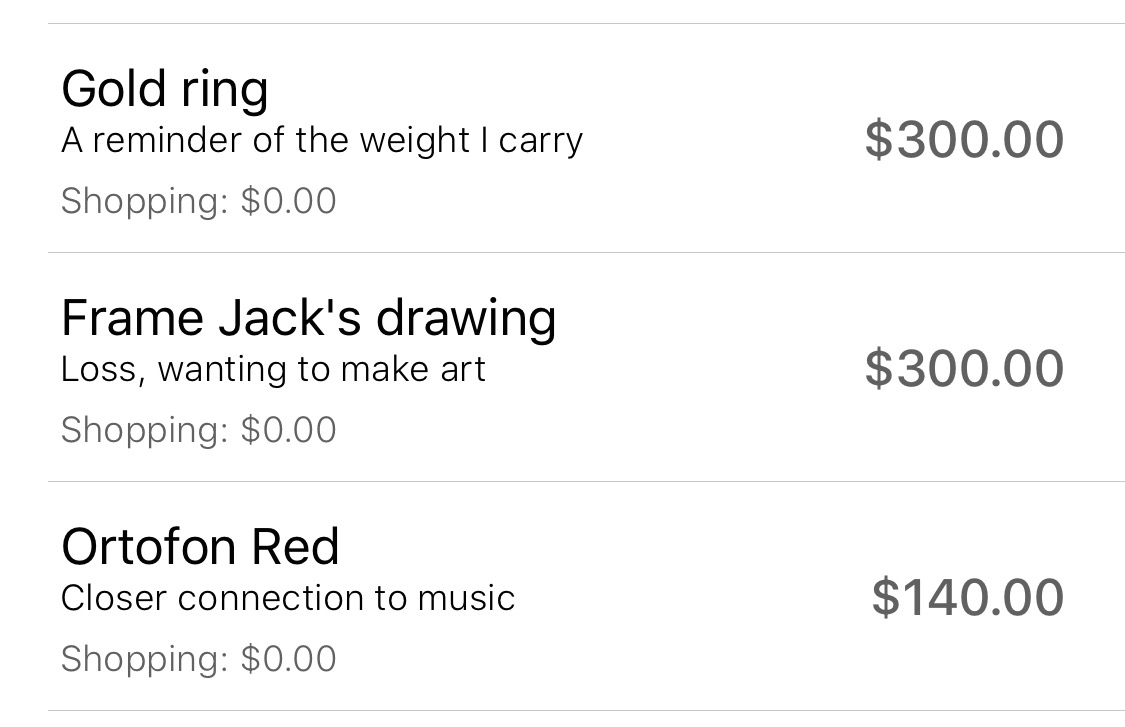

To do that, I added a small field that lets me write out what need this thing promises to fulfill for me. It then shows up inline in the list of all the tasks. If nothing else, it means I’m gonna be more aware of what I’m paying to satisfy, but even then, I think it’ll prompt me to be more connected to myself.

Yeah, those are cheesy notes. That’s what feelings look like in sentence-long summaries. A fish that fights you doesn’t necessarily look nice after you caught it, but that’s not really the point, is it? It’s that you caught the fish. I reeled in these fucking feelings. I finally did. And now, the world looks very different, and they’re on everything I never thought they had anything to do with, like fish scales after you scale an ugly, big fish.

Something I realized recently is that I’ve always had these feelings, these needs, these wants. I just wasn’t allowed to have them or pursue them. I had to take them and redirect them to whatever was safe: school, my career, or towards other people who could do what I really wished for myself.

It’s been like that for a long time. Money’s just one of many ways my wants got displaced onto something more available than my feelings. When I was a kid, the document I put most of my time into was my Christmas wishlist. I learned all the fine arts of Microsoft Office to create a totem in honour of the self that I was looking for any excuse to surface and prioritize and show.

But even still, that’s something. Good job, little Andrew. If you put everything you wish for in a list, even a list that’s ostensibly a shopping list, even if it might look like a budget app, you might learn what you want, and you might even get it. But not necessarily the way you expect. I might look at that $140 Ortofon Red turntable cartridge in my Ynabby app in a year and delete it not because I bought it, but because I found the thing in me that was asking for it, and had found a way to give myself what I really needed, instead.

And maybe I’ll buy it, too. Who knows. Sometimes, a pipe is just a pipe. Sometimes, a dollar spent in pursuit of a full and gorgeous life can make that life two dollars richer.

Subscribe to hear more

I’m gonna keep writing about my weird lessons from my weird apps. If you’d like to hear more about where this goes – and maybe try my apps for yourself – just put in your email here: